Menu

Menu

—

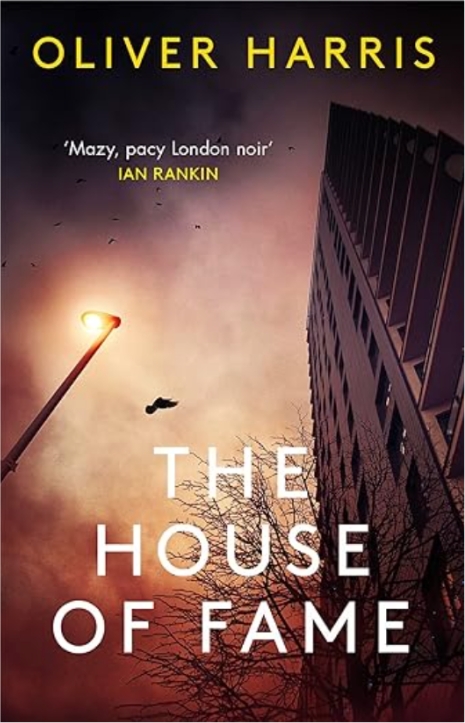

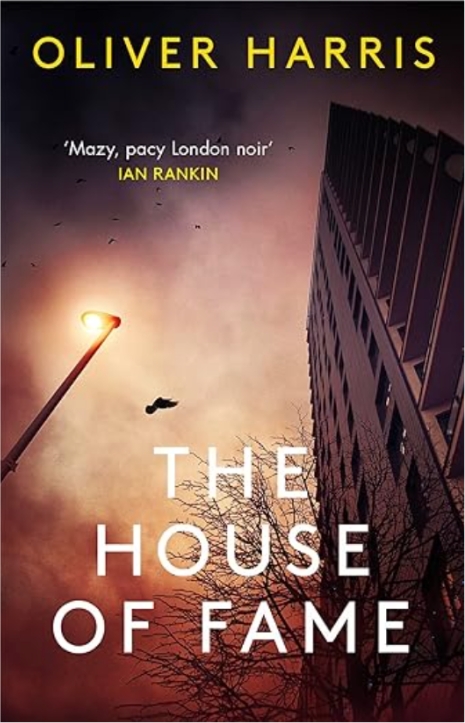

Amber Knight is hot property – pop star, film star, front-page gossip.

DC Nick Belsey is less celebrated. He can’t shake his habit of getting into serious trouble and his career at Hampstead CID is coming to a dishonourable end. He is currently of no fixed address – squatting in a disused police station round the corner from Amber’s swanky Primrose Hill mansion.

But a knock on the door from a frantic and confused woman looking for her missing son is about to lead Belsey straight into the heart of Amber’s glittering life. When a body is found and a twisted crime spree ensues, Belsey finds himself dangerously embroiled in a world of celebrity, obsession, glamour and desperation.

‘Meticulously plotted, with a delirious, haunted, paranoid atmosphere. Belsey is an irresistible mixture of the reliable and the reckless, laconic and tightly wound… Harris writes beautifully… Imbued with an uncommon subtlety and intelligence, House of Fame is a superb novel.’

‘A fast-paced thriller that is also nuanced and evocative…hats off to Harris, who has, once again, managed it with style and authority.’

‘Gripping… Oliver Harris is punchy and perceptive.’

‘Harris has a terrific sense of place, hurtling between the wealthiest and most-run-down areas of London… The plot unfolds in a chilling and totally unexpected direction.’

Extract from the book

They’d cut the electricity. Mid-morning the sun hit the CID office, sliced by the window’s metal screen into planes of tobacco smoke and dust. By 3 p.m. it reached the back of the building: Belsey liked to open the doors on the first-floor corridor so light stretched from the kitchen to the interview rooms. Long lozenges of gold slipped across the chipped walls, made the place feel less abandoned. It created a sundial around him. He sat on the floor and watched it all. Caught in the bars of light, the dust seemed frenzied, directionless. His smoke rolled through it. He used the clocks as ashtrays.

Hampstead police station had closed three weeks ago, one of six across London disposed of in cost-cutting measures. Most staff had been reassigned at the end of last year. Belsey had expected to go to Holborn, but nothing happened. The DI at Holborn said they’d tried to get him only to be told he was blocked. Then, ten days after the station closed, he was informed he’d been officially suspended pending a hearing over allegations of gross misconduct. No details. A few hours after that, he got a call from a man who wouldn’t give his name but told him he was under surveillance: the Independent Police Complaints Commission were collecting ammo, approaching everyone from Belsey’s exes to his past informers, putting obs on his car, his local, his current landlord. They were bracing themselves for a shit-storm. Stay safe, the caller said, and hung up. An hour later Belsey withdrew the contents of his current account, bought a gas stove, three bottles of Havana Club and a book – Teach Yourself Spanish. He broke into his old place of work, changed the locks. It was, he felt, the last place they’d look for him.

Eleven days ago.

It had been an odd stretch of time. Sometimes he found himself following patterns of an old routine, standing in the CID kitchen at ten-thirty making a tea; lying on the floor of the old meeting room watching the wiring exposed by missing ceiling panels. He’d wander the station. The building dated to 1913, a labyrinthine relic with adjoining courthouse and cells. Most of it had been disused for decades. But in the process of clearing out, older areas had been unlocked: the abandoned station had grown, extending itself back into the past. Belsey walked through the magistrate’s court to an Edwardian custody suite, past old fuse switches to cells that had become carpeted in handwritten reports from the 1950s and ’60s: loose, yellowed papers, notebooks with cracked leather covers like shells. They had spilled from rat-chewed cardboard boxes, an infestation, filled with the handwriting of dead policemen. Sometimes he’d skim through old cases to keep his mind occupied. There were unnerving moments, once or twice a day, when it felt as if he was meant to be here after all, assigned for reasons that had faded. The thick old glass made the place feel submarine. His kingdom until ten minutes ago, when someone had started knocking on the front door.

The steady insistence of the knocks was troubling. Ceremonious. A ceremony he was failing to perform: the coming of reality. He knew that this last misdemeanour, like the rest, had been a taunt, the gambler’s desire to suspend the moment of reckoning, to conjure 3 options from nothing. The knocking was at the main entrance, directly beneath the CID office. Belsey looked down through the shutters but the angle was too tight. The sign down there was clear enough: Hampstead police station is now closed. Your nearest station is Kentish Town. No one knew where he’d chosen to lie low. But the knocking felt like the return of something he’d forgotten: a debt, an arrangement, a plan of action.